If you're a frontend developer, you know that one of the scariest tasks you can receive is coding a complex web animation. If you're not a frontend developer, I bet that sounds even harder.

Don't get me wrong, I love web animations! They are an elegant way to show off some flair in your website when used correctly. And unlike traditional animation media, they can even be interacted with, giving it a bit of personal flair.

But animating on the web also has its limitations, and the challenges they make you face can be quite daunting. So when our amazing design team shared me previews for the new animations that I'd be working on, I started thinking they didn't like me very much.

I jest, I was super stoked! The animations looked fantastic. But I'm not joking when I say that they were much more challenging than I initially thought.

What are we animating?

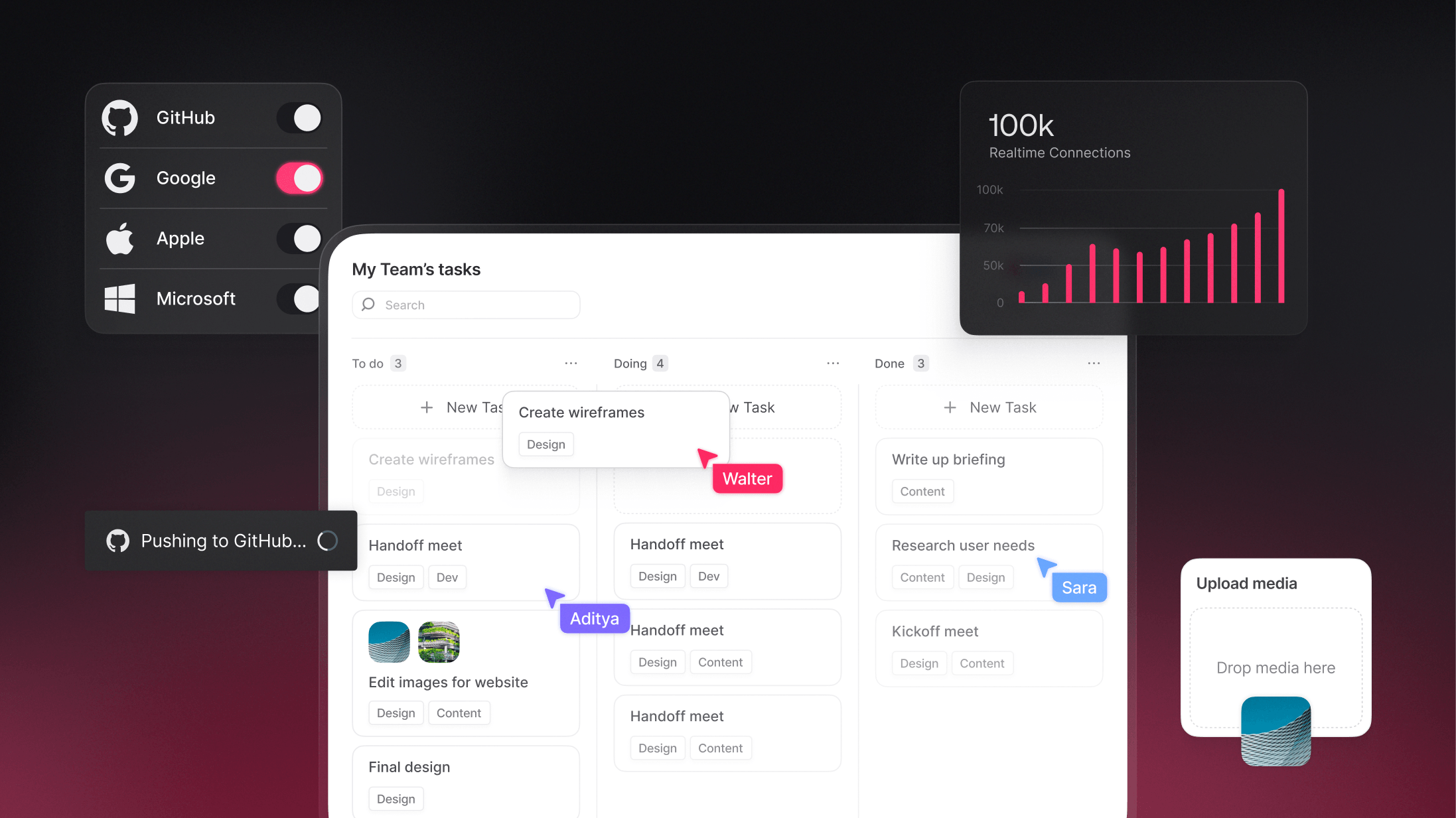

First things first, what was I supposed to animate? Well, in this article, I'll be mainly talking about this animation, that's present at Appwrite's homepage.

There's a lot of stuff going on in there! There are multiple sections, each one with possible interactivity, and there's also animation between the sections, where the phone moves positions.

There's a lot to digest here, so let's break this into parts. We need to code:

The logic that activates a section based on the scroll position

Each individual section's animation

How to animate between sections

Let's get into it!

P.S. The code for the website, including animations, can be found at https://github.com/appwrite/website/.

Excuse me, scrolling through!

Scroll-based animations are quite common. There are two types. Animations that start when you scroll to a certain section, and animations that progress together with your scroll. For our animations, we're using the former.

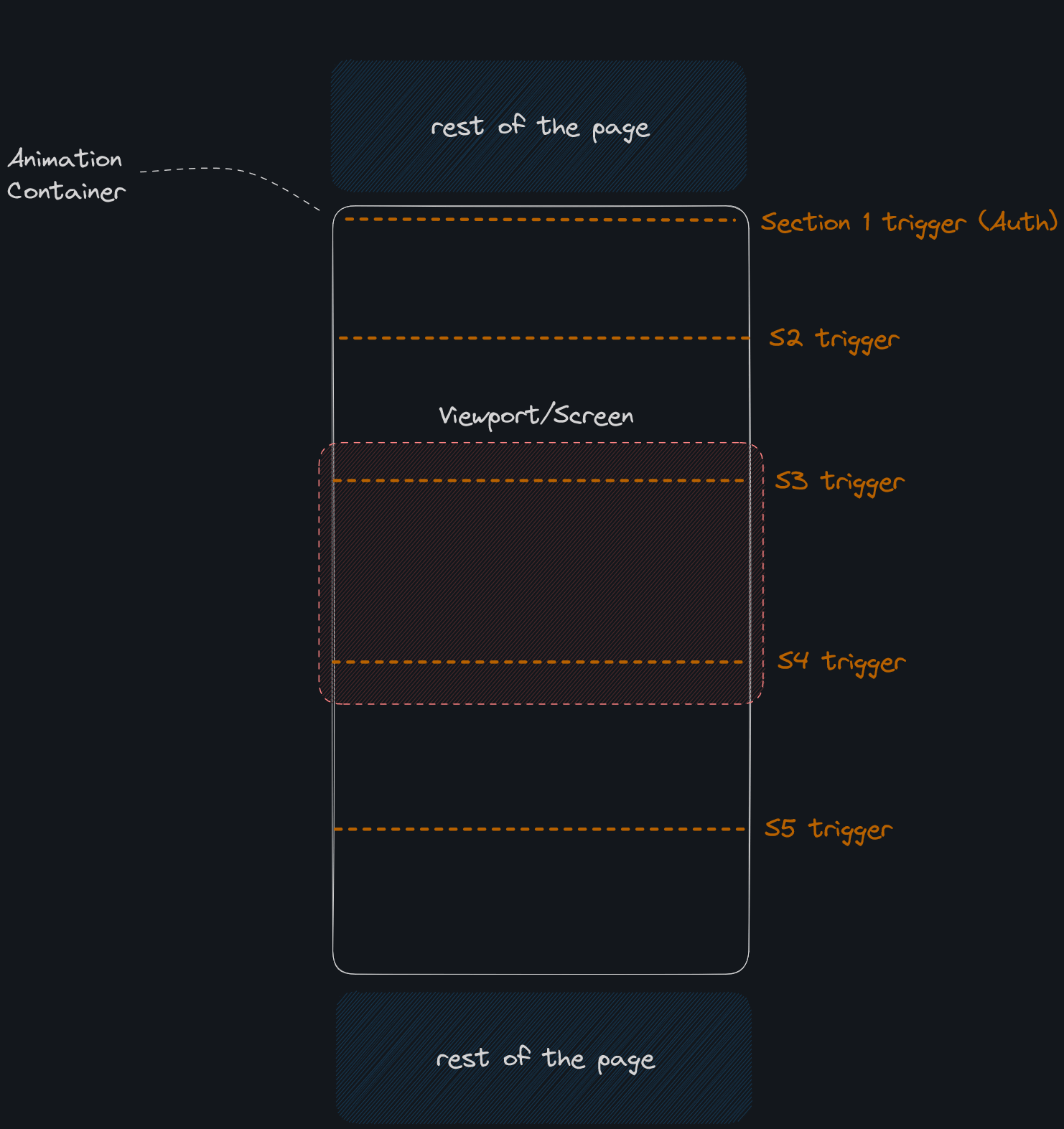

We have 5 sections in our animation, as showcased in our video (we technically have 2 more, one for the beginning and one for the end), and they're pretty similar. They are all in a really tall container, so that we have ample space to scroll through, but the animations themselves always stick to the center of the screen.

I've split said container into 5 equal parts, each part representing a section. All the sections are always sticking to the center of the screen as I said, but, once the top of the viewport passes a section trigger, the respective section is active, and all the other sections are de-activated. (In the sketch above, the active section is the 2nd one, but if the user scrolls down just a bit, the 3rd section will be active.)

I decided to create a helper function that, given an HTML element, returns what percentage has been traversed. With that, I can apply the function to our AnimationContainer, and determine what's the active section. E.g. since the triggers are at 0%, 20%, 40%, 60% and 80%, if we've already traversed 50% of the viewport, Then I know that the third section is the one that's active.

For the curious minds, here's what the function looks like:

import type { Action } from "svelte/action";

export type ScrollInfo = {

percentage: number;

traversed: number;

remaning: number;

};

export const scroll: Action<

HTMLElement,

undefined,

{

"on:web-scroll": (e: CustomEvent<ScrollInfo>) => void;

"on:web-resize": (e: CustomEvent<ScrollInfo>) => void;

}

> = (node) => {

function getScrollInfo(): ScrollInfo {

const { top, height } = node.getBoundingClientRect();

const { innerHeight } = window;

const scrollHeight = height - innerHeight;

const scrollPercentage = (-1 * top) / scrollHeight;

const traversed = scrollPercentage * scrollHeight;

const remaning = scrollHeight - traversed;

return {

percentage: scrollPercentage,

traversed,

remaning,

};

}

const createHandler = (eventName: "web-scroll" | "web-resize") => {

return () => {

node.dispatchEvent(

new CustomEvent<ScrollInfo>(eventName, {

detail: getScrollInfo(),

})

);

};

};

const handleScroll = createHandler("web-scroll");

const handleResize = createHandler("web-resize");

handleScroll();

handleResize();

window.addEventListener("scroll", handleScroll);

window.addEventListener("resize", handleResize);

return {

destroy() {

window.removeEventListener("scroll", handleScroll);

window.removeEventListener("resize", handleResize);

},

};

};

You'll notice however, that this is not just a regular function. It's a Svelte Action. From the docs:

Actions are functions that are called when an element is created. They can return an object with a destroy method that is called after the element is unmounted.

In practice, what this means is, given this syntax:

<div id="products" use:scroll on:web-scroll={(e) => scrollInfo = e.detail}>

<!-- ... -->

</div>

The function will automatically run with the given div being passed in as the node parameter. And whenever that div is unmounted from the DOM, the destroy function will be run. This allows us to easily create reusable functions that directly interact with the DOM with almost no boilerplate!

Hand-crafting individual animations

We now go to the core of the animation process: Actually animating it.

There are several tools you can use to your disposal for crafting web animations. For Pink's website, we opted to use CSS animations, for the most part. The exception was a typing animation in the code, which is not normally achievable with CSS.

In this case though, we have decided to go full JS for our animations. The reason is that, we'd already require some JS for the elements that require interactivity, and it's much easier orchestrating a series of animations that run one after another in JS, than in CSS.

We've decided to use Motion, a library which wraps around the Web Animations API. It allows us to write a animation for a section in a pretty intuitive way:

async function authAnim() {

await animate(box, { y: [48, 140], opacity: 1 }, { duration: 0.25, delay: 0.25 }).finished;

safeAnimate(phone, { x: 0, y: 0 }, { duration: 0.5 }),

safeAnimate(controls, { x: 420, y: 0, opacity: 0 }, { duration: 0.5 })

}

In the example above, the boxelement will animate and only after it finished animating, will the other elements animate, simultaneously.

But that's not all we used. We also took heavy advantage of Svelte's in-built transition directives, which automatically animate elements when they enter or exit the DOM, and also allow us to move surrounding elements that are affected by the new elements, e.g. when entering a list.

The video above showcases both Motion and Svelte transitions in action. The table and code box enter animations are controlled by Motion, while the new user entering the table is animated by Svelte, as well as the OAuth options.

<!-- Svelte Animations -->

<button class="sign-up">Sign Up</button>

{#if controlsEnabled}

<span class="with-sep" transition:fade={{ duration: 100 }}>or sign up with</span>

<div class="oauth-btns" transition:fade={{ duration: 100 }}>

{#each objectKeys($state.controls).filter((p) => $state.controls[p]) as provider (provider)}

<button class="oauth" transition:fade={{ duration: 100 }} animate:flip={{ duration: 250 }}>

<div class="inner">

<span class="web-icon-{provider.toLowerCase()}" />

<span>{provider}</span>

</div>

</button>

{/each}

</div>

{/if}

Transitioning between sections

There's one other nifty feature of Motion that I didn't mention: It can seamlessly interrupt ongoing animations.

To illustrate this scenario, imagine you have two animations, one that moves Box from a point x: 0to x: 64, and another that does the opposite. Now, you start the first animation, but in the middle of it you trigger the second animation, when Boxis at x: 32. Ideally, what would happen? To have a seamless transition, it should go from x: 32back to x: 0. But normally, with CSS keyframes, the Boxelement would jump to x: 64, and then animate to x: 0.

Here's an example. It uses CSS transitions for the seamless bit, which may raise the question: Why not use it instead of Motion? And the answer is, it's still a bit awkward to use. You'd have to define a CSS class for every transition, define it in the style tag, and then change it in the DOM. You also don't have a way in JS to know it has ended without hard-coding the transition duration.

Going back to our own animations then, on the start of each section animation, we reset the elements back to their starting elements.

const { update } = state.reset();

await Promise.all([

animate(box, { x: 310, y: 140, opacity: 0 }, { duration: 0.5 }).finished,

animate(code, { x: 200, y: 460, opacity: 0 }, { duration: 0.5 }).finished,

animate(phone, { x: 0, y: 0 }, { duration: 0.5 }).finished,

animate(controls, { x: 420, y: 0, opacity: 0 }, { duration: 0.5 }).finished

]);

This allows Motion to seamlessly transition between the current animation state of the elements into the new ones.

There's still an elephant in the room though... We're using async functions. If the function is still running, and I go into a new section, that means that two functions will be running that control the same element! How come the animations don't clash?

To deal with that, we use dynamic references to our elements. Each element has an id, with a number suffixed to it, e.g. #box-1. Whenever the section changes, we add 1 to the suffix, e.g. #box-2. And at the start of any section animation, we get the element ID at that given point in time, and then don't re-request the ID.

How does this look in practice? If I'm starting Section 1's animation, this is at the beginning of my async function.

const box = getElSelector('box'); // #box-1

Now, even if I start Section 2, and the selector gets updated, the constant boxis still #box-1. The function is running, but trying to animate based on a selector that will not resolve to any element! And we can continue without fear, pretending the async functions have been canceled, defying the laws of what normally is possible within web animations!

But, we also modify Svelte stores in our animation functions. How do we avoid clashes there? Well, you may notice this piece of code in one of the earlier snippets:

const { update } = state.reset();

This comes from a custom store I built, called resettable. It works similarly to our selector! It has an internal ID, which gets updated whenever we call reset. That reset method returns a scoped updatefunction, that checks if the current ID of the resettable store is the same as the one that got created when we called reset. If it's not, it doesn't update the store.

This is what the code looks like:

const simpleUUID = () => {

return (

Math.random().toString(36).substring(2, 15) + Math.random().toString(36).substring(2, 15)

);

};

export const createResettable = <Value>(defaultValue: Value) => {

type SubscribeCallback = (v: Value) => void;

let subscribeCallbacks: SubscribeCallback[] = [];

let currUuid = simpleUUID();

let state = structuredClone(defaultValue);

const subscribe = (cb: SubscribeCallback) => {

subscribeCallbacks.push(cb);

cb(state);

return () => {

subscribeCallbacks = subscribeCallbacks.filter((c) => c !== cb);

};

};

const reset = () => {

currUuid = simpleUUID();

const fixedId = currUuid;

const set = (v: Value) => {

if (fixedId !== currUuid) return;

state = v;

subscribeCallbacks.forEach((cb) => cb(state));

};

const update = (fn: (v: Value) => Value) => {

set(fn(state));

};

set(structuredClone(defaultValue));

return { set, update };

};

return {

subscribe,

reset,

set: (v: Value) => {

state = v;

subscribeCallbacks.forEach((cb) => cb(state));

},

update: (fn: (v: Value) => Value) => {

state = fn(state);

subscribeCallbacks.forEach((cb) => cb(state));

}

};

};

Combining resettable with getElSelectorand Motion, ensures smooth transitions between all sections!

Wrapping it up

We've gone over the building blocks of our main animations: Triggering an animation on scroll, coding said animation, and enabling the transition between multiple animations. Join them all up, and we've just transformed a designer's dream into reality!

I hope this article helped outline the thought process behind this challenge, and also motivates you to delve into our source code to discover other nifty tricks we did to make our website possible!

Happy hacking!