The Database is one of the cornerstones of every application. It's where you store everything your app needs to remember, compute later, or display to other users online. It's all smooth sailing until your database grows and your application starts lagging because it's trying to fetch and render 1,000 posts simultaneously. As a smart engineer, you quickly patch this with a Show more button. However, a few weeks later, you encounter a Timeout error. Turning to Stack Overflow, you find that copying and pasting solutions is no longer helping. With no other options, you start debugging and discover that the database returns over 50,000 posts each time a user opens your app. What do you do now?

To avoid these challenging scenarios, it’s important to be aware of potential risks from the start. A well-prepared developer can mitigate these issues. This article will help you address database-related performance problems using offset and cursor pagination.

What is pagination?

Pagination is a strategy employed when querying any dataset that holds more than just a few hundred records. Thanks to pagination, we can split our large dataset into chunks that we can gradually fetch and display to the user, thus reducing the load on the database. Pagination also solves a lot of performance issues both on the client and server-side! Without pagination, you'd have to load the entire chat history only to read the latest message sent to you.

These days, pagination has almost become a necessity since every application is very likely to deal with large amounts of data. This data could be anything from user-generated content, content added by administrators or editors, or automatically generated audits and logs. As soon as your list grows to more than a few thousand items, your database will take too long to resolve each request and your front-end's speed and accessibility will suffer.

Now that we know what pagination is, how do we actually use it? And why is it necessary?

Types of pagination

Two widely used pagination strategies are offset and cursor. Before learning everything about them, let's look at some websites using them.

First, let's visit GitHub's Stargazer page. Notice how the tab says 5,000+, not an absolute number. Also, instead of standard page numbers, they use Previous and Next buttons.

Now, let's switch to Amazon's products list and notice the exact number of results: 364. Standard pagination with all page numbers you can click through is 1 2 3 ... 20.

It's clear that two tech giants could not agree on which solution is better! Why? Well, we'll need to use an answer developers hate: It depends. Let's explore both methods to understand their advantages, limitations, and performance implications.

Offset pagination

Most websites use offset pagination because of its simplicity and how intuitive pagination is to users. To implement offset pagination, we will usually need two pieces of information:

limit - Number of rows to fetch from the database

offset - Number of rows to skip. Offset is like a page number but with a bit of math around it (offset = (page-1) * limit)

To get the first page of our data, we set the limit to 10 (because we want 10 items on the page) and offset to 0 (because we want to start counting 10 items from the 0th item). As a result, we will get ten rows.

To get the second page, we keep the limit at 10 (this doesn't change since we want every page to contain 10 rows ) and set the offset to 10 ( return results from the 10th row onwards. We continue this approach thereby allowing the end user to paginate through the results and see all of their content.

In the SQL world, such a query would be written as SELECT * FROM posts OFFSET 10 LIMIT 10.

Some websites implementing offset pagination also show the page number of the last page. How do they do it? Alongside results for each page, they also tend to return a sum attribute telling you how many rows there are in total. Using limit, sum, and a bit of math, you can calculate last page number using lastPage = ceil(sum / limit)

As convenient as this feature is for the user, developers struggle to scale this type of pagination. Looking at sum attribute, we can already see that it can take quite some time to count all rows in a database to the exact number. Alongside that, the offset in databases is implemented in a way that loops through rows to know how many should be skipped. That means that the higher our offset is, the longer our database query will take.

Another downside of offset pagination is that it doesn't play well with real-time data or data that changes often. Offset says how many rows we want to skip but doesn't account for row deletion or new rows being created. Such an offset can result in showing duplicate data or missing data.

Cursor pagination

Cursors are successors to offsets, as they solve all issues that offset pagination has - performance, missing data and data duplication because it does not rely on the relative ordering of the rows as in the case of offset pagination. Instead, it relies on an index created and managed by the database. To implement cursor pagination, we will need the following information:

limit - Same as before, the number of rows we want to show on one page

cursor - ID of a reference element in the list. This can be the first item if you're querying the previous page and the last item if querying the next page.

cursorDirection - If a user clicks Next or Previous (after or before)

When requesting the first page, we don't need to provide anything, just the limit 10, saying how many rows we want to get. As a result, we get our ten rows.

To get to the next page, we use the ID of the last row as the cursor and set cursor direction to after.

Similarly, if we want to go to the previous page, we use the ID of the first row as a cursor and set the direction to before.

To compare, in the SQL world, we could write our query as SELECT * FROM posts WHERE id > 10 LIMIT 10 ORDER BY id DESC.

Queries that use a cursor instead of offset are more performant because the WHERE query helps skip unwanted rows, while OFFSET needs to iterate over them, resulting in a full-table scan. Skipping rows using WHERE can get even faster if you set up proper indexes on your IDs. The index is created by default in the case of your primary key.

Not only that, you no longer need to worry about rows being inserted or deleted. If you were using an offset of 10, you would expect exactly 10 rows to be present ahead of your current page. If this condition is not met, your query will return inconsistent results, leading to data duplication and even missing rows. This can happen if any of the rows ahead of your current page are deleted or new rows are added. Cursor pagination solves this by using the index of the last row you fetched, and it knows exactly where to start looking from when you request for more.

However, cursor pagination is a complex problem if you need to implement it on the backend. To implement cursor pagination, you will need WHERE and ORDER BY clauses in your query. In addition, you will also need WHERE clauses to filter by your required conditions. This can get quite complex very quickly, and you might end up with a huge nested query. You will also need to create indexes for all the columns you need to query.

Now that you have eliminated duplicates and missing data by switching to cursor pagination, you still have one problem left. Since you should not expose incremental numeric IDs to the user (for security reasons), you must now maintain a hashed version of each ID. Whenever you need to query a database, you convert this string ID to its numeric ID by looking at a table that holds these pairs. What if this row is missing? What if you click the Nextbutton, take the last row's ID, and request the next page, but the database can't find the ID?

This is a really rare condition and only occurs if the row's ID that you are about to use as a cursor has been just deleted. We can solve this problem by trying previous rows or re-fetching data of earlier requests to update the last row with a new ID, but all of that brings a whole new level of complexity, and the developer needs to understand a bunch of new concepts, such as recursion and proper state management. Thankfully, services such as Appwrite take care of that, so you can simply use cursor pagination as a feature.

Pagination in Appwrite

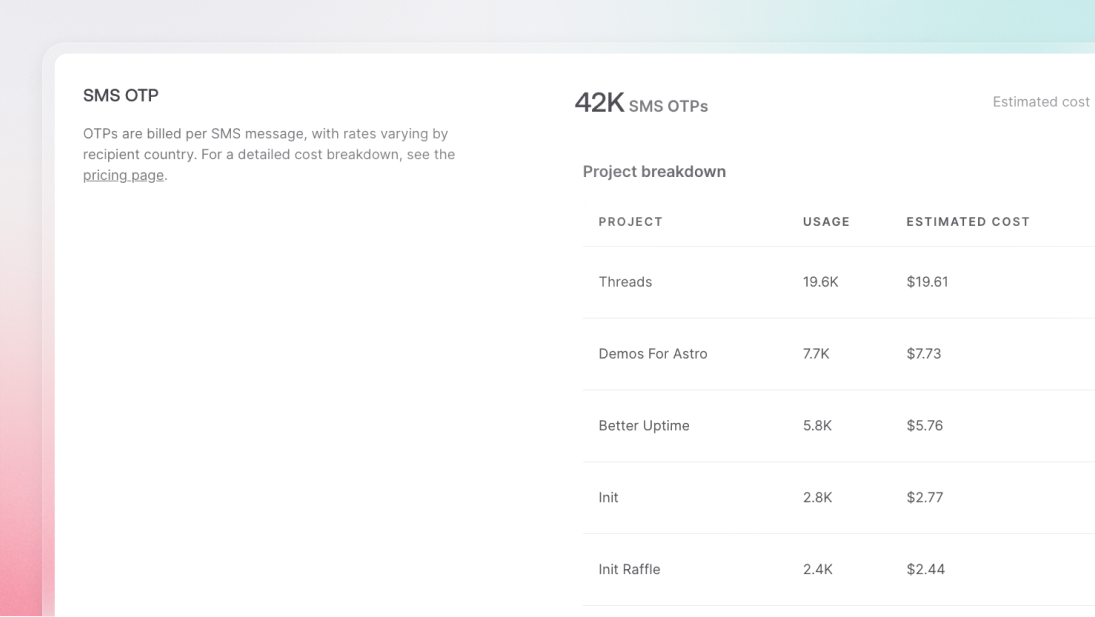

Appwrite is an open-source backend-as-a-service that abstracts all the complexity involved in building a modern application by providing you with a set of REST APIs for your core backend needs. Appwrite handles user authentication and authorization, databases, file storage, cloud functions, webhooks, messaging, and more. You can extend Appwrite using your favorite backend language if anything is missing.

Appwrite Database lets you store any text-based data that needs to be shared across your users. Appwrite's database allows you to create multiple collections (tables) and store multiple documents (rows) in it. Each collection has attributes (columns) configured to give your dataset a proper schema. You can also configure indexes to make your search queries more performant. When reading your data, you can use powerful queries, filter them, sort them, limit the number of results, and paginate over them.

Appwrite's pagination supports both offset and cursor pagination. Let's imagine you have a collection with ID articles. You can get documents from this collection with either offset or cursor pagination:

// Setup

import { Appwrite, Databases, Query } from "appwrite";

const client = new Appwrite();

client

.setEndpoint('https://cloud.appwrite.io/v1') // Your API Endpoint

.setProject('articles-demo'); // Your project ID

const databases = new Databases(client);

// Offset pagination

databases.listDocuments(

'main', // Database ID

'articles', // Collection ID

[

Query.limit(10), // Limit, total documents in the response

Query.offset(500), // Offset, amount of documents to skip

]

).then((response) => {

console.log(response);

});

// Cursor pagination

databases.listDocuments(

'main', // Database ID

'articles', // Collection ID

[

Query.limit(10), // Limit, total documents in the response

Query.cursorAfter('61d6eb2281fce3650c2c', // ID of document I want to paginate after

]

).then((response) => {

console.log(response);

});

First, we import the Appwrite SDK and set up an instance that connects to our Appwrite Cloud project. Then, we list 10 documents using offset pagination. Right after, we write the exact same list documents query, but this time using cursor instead of offset pagination.

Benchmarks

We’ve frequently mentioned the term "performance" in this article without providing specific numbers, so let’s create a benchmark together. We'll use Appwrite as our backend server, as it supports both offset and cursor pagination, and Node.js for writing the benchmark scripts, as JavaScript is straightforward to follow.

You can find complete source code in the GitHub repository.

First, you set up Appwrite, register a user, create a project and create a collection called posts with read permission set to any. To learn more about this process, visit the Appwrite docs. You should now have Appwrite ready to go.

Use the following script to load data into our MariaDB database and prepare for the benchmark. We could use Appwrite SDK, but talking directly to MariaDB offers more optional write queries for large datasets.

const config = {};

// Don't forget to fill config variable with secret information

console.log("🤖 Connecting to database ...");

const connection = await mysql.createConnection({

host: config.mariadbHost,

port: config.mariadbPost,

user: config.mariadbUser,

password: config.mariadbPassword,

database: `appwrite`,

});

const promises = [];

console.log("🤖 Database connection established");

console.log("🤖 Preparing database queries ...");

let index = 1;

for(let i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

const queryValues = [];

for(let l = 0; l < 10000; l++) {

queryValues.push(`('id${index}', '[]', '[]')`);

index++;

}

const query = `INSERT INTO _project_${config.projectId}_collection_posts (_uid, _read, _write) VALUES ${queryValues.join(", ")}`;

promises.push(connection.execute(query));

}

console.log("🤖 Pushing data. Get ready, this will take quite some time ...");

await Promise.all(promises);

console.error(`🌟 Successfully finished`);

We used two layers for loops to increase the speed of the script. First for loop creates query executions that need to be awaited, and the second loop creates a long query holding multiple insert requests. Ideally, we would want everything in one request, but that is impossible due to MySQL configuration, so we split it into 100 requests.

Now you have 1 million documents inserted in less than a minute, and are ready to start the benchmarks. We will be using the k6 load-testing library for this demo.

Let's benchmark the well-known and widely used offset pagination first. During each test scenario, we try to fetch a page with 10 documents, from different parts of our dataset. We will start with offset 0 and go all the way to an offset of 900k in increments of 100k. The benchmark is written in a way that makes only one request at a time to keep it as accurate as possible. We will also run the same benchmark ten times and measure average response times to ensure statistical significance. We'll be using k6's HTTP client to make requests to Appwrite's REST API.

// script_offset.sh

import { Query } from 'appwrite';

import http from 'k6/http';

// Before running, make sure to run setup.js

export const options = {

iterations: 10,

summaryTimeUnit: "ms",

summaryTrendStats: ["avg"]

};

const config = JSON.parse(open("config.json"));

export default function () {

const offset = Query.offset(__ENV.OFFSET);

const limit = 10;

http.get(`${config.endpoint}/databases/main/collections/posts/documents?queries[]=${offset}&queries[]=${limit}`, {

headers: {

'content-type': 'application/json',

'X-Appwrite-Project': config.projectId

}

});

}

To run the benchmark with different offset configurations and store output in CSV files, I created a simple bash script. This script executes k6 ten times, with a different offset configuration each time. The output will be provided as console output.

#!/bin/bash

# benchmark_offset.sh

k6 -e OFFSET=0 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=100000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=200000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=300000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=400000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=500000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=600000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=700000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=800000 run script.js

k6 -e OFFSET=900000 run script.js

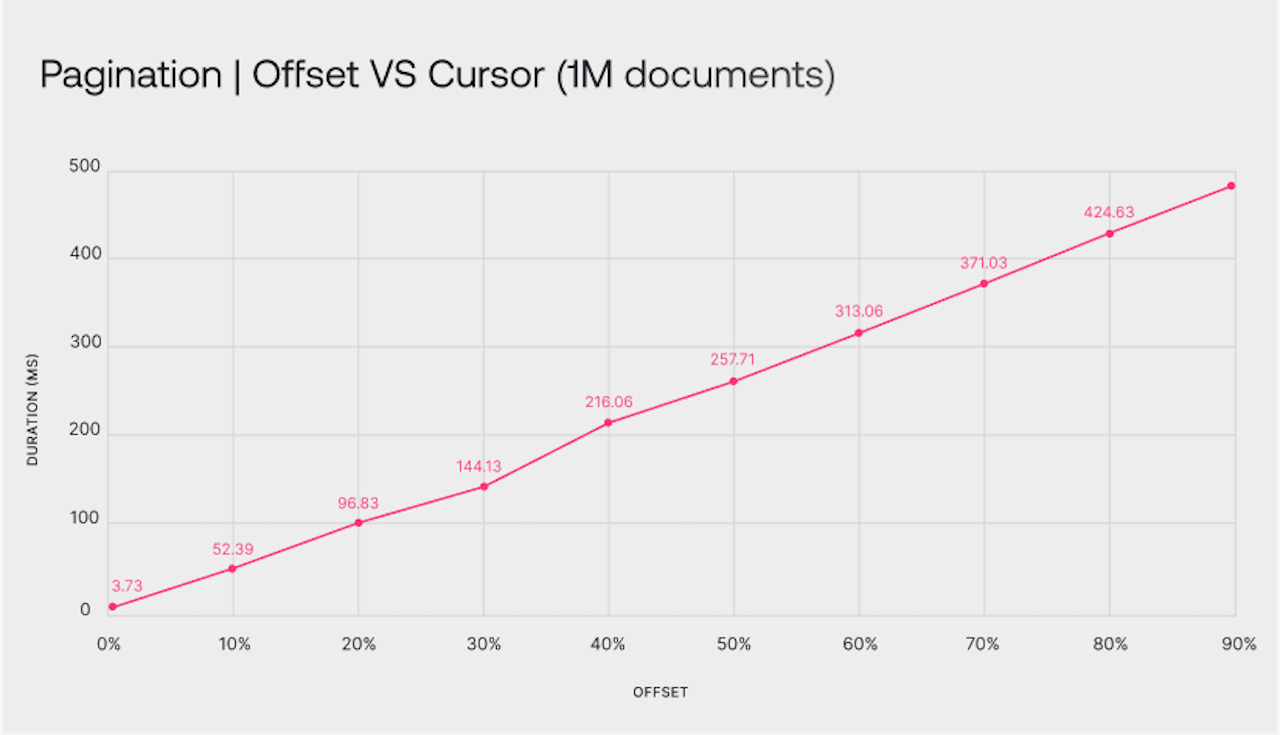

Within a minute, all benchmarks finished, providing me with the average response time for each offset configuration. The results were as expected but not satisfying at all.

| Offset pagination (ms) | |

| 0% offset | 3.73 |

| 10% offset | 52.39 |

| 20% offset | 96.83 |

| 30% offset | 144.13 |

| 40% offset | 216.06 |

| 50% offset | 257.71 |

| 60% offset | 313.06 |

| 70% offset | 371.03 |

| 80% offset | 424.63 |

| 90% offset | 482.71 |

Now let's update our script to use cursor pagination. We will update our script to use a cursor instead of offset and update our bash script to provide a cursor (document ID) instead of an offset number.

// script_cursor.js

import { Query } from 'appwrite';

import http from 'k6/http';

// Before running, make sure to run setup.js

export const options = {

iterations: 10,

summaryTimeUnit: "ms",

summaryTrendStats: ["avg"]

};

const config = JSON.parse(open("config.json"));

export default function () {

const cursor = Query.cursorAfter(__ENV.CURSOR);

const limit = 10;

http.get(`${config.endpoint}/databases/main/collections/posts/documents?queries[]=${offset}&queries[]=${limit}`, {

headers: {

'content-type': 'application/json',

'X-Appwrite-Project': config.projectId

}

});

}

#!/bin/bash

# benchmark_cursor.sh

k6 -e CURSOR=id1 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id100000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id200000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id300000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id400000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id500000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id600000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id700000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id800000 run script_cursor.js

k6 -e CURSOR=id900000 run script_cursor.js

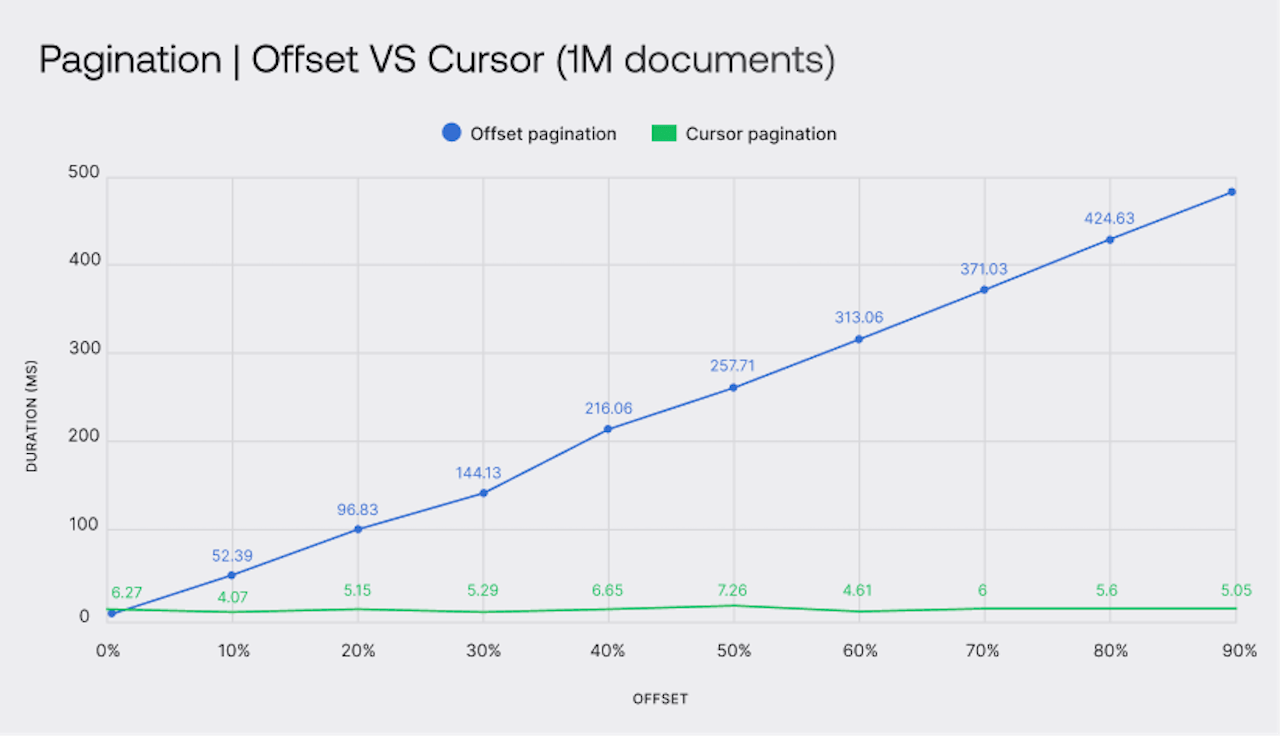

After running the script, you could already tell that there was a performance boost, as there were noticeable differences in response times. Take a look at this table to compare the two pagination methods side-by-side.

| Offset pagination (ms) | Cursor pagination (ms) | |

| 0% offset | 3.73 | 6.27 |

| 10% offset | 52.39 | 4.07 |

| 20% offset | 96.83 | 5.15 |

| 30% offset | 144.13 | 5.29 |

| 40% offset | 216.06 | 6.65 |

| 50% offset | 257.71 | 7.26 |

| 60% offset | 313.06 | 4.61 |

| 70% offset | 371.03 | 6.00 |

| 80% offset | 424.63 | 5.60 |

| 90% offset | 482.71 | 5.05 |

As you can see, cursor pagination is highly efficient. The graph shows that cursor pagination maintains consistent performance regardless of the offset size, with each query performing as well as the first or last one. Loading the last page of a large list repeatedly can significantly impact performance.

If you are interested in running tests on your own machine, you can find the complete source code in a GitHub repository. The repository includes README.md, which explains the installation and running of scripts.

Conclusion

Offset pagination offers a well-known pagination method where you can see page numbers and click through them. This intuitive method comes with a bunch of downsides, such as terrible performance with high offsets and a chance of data duplication and missing data.

Cursor pagination solves all of these problems and brings a reliable pagination system that is fast and can handle real-time (often changing) data. The downside of cursor pagination is not showing page numbers, its implementation complexity, and a new set of challenges to overcome, such as missing cursor ID.

Let's now get back to our original question: Why does GitHub use cursor pagination, but Amazon decided to go with offset pagination? Performance is not always the key. User experience is much more valuable than how many servers your business has to pay for.

I believe Amazon decided to go with offset because it improves UX, but that is a topic for another research. We can already notice that if we visit amazon.com and search for a pen, it says there are exactly 10 000 results, but you can only visit the first seven pages (350 results).

First, there are far more than 10,000 results, but Amazon imposes a limit. Secondly, you can only access the first seven pages; attempting to visit page 8 results in a 404 error. This indicates that Amazon is aware of the performance issues with offset pagination but continues to use it because users prefer seeing page numbers. They had to implement some limits, but it's unlikely that users navigate to page 100 of the search results.

Do you know what is better than reading about pagination? Trying it out! I would encourage you to try both methods because it's best to get first-hand experience. Setting up Appwrite takes less than a few minutes, and you can start playing with both pagination methods. If you have any questions, you can also reach us on our Discord server.